Resting Posture

It is important to understand that the posture in which you go through life (let’s call it “resting posture”) must be different from an engaged, active posture. Every activity has specific mechanics that are advantageous, but in a basic sense, anything that requires a high degree of bracing and stabilization will have certain shared postural elements (engaged abdominals, retracted scapulae, straight spine). Applying these principles to “resting posture” (henceforth RP for the duration of this post) will typically layer dysfunction upon dysfunction.

**There are a lot of concepts involved in this, because the body is not simple. Try and persevere through if theses concepts are new to you, and if you have questions, contact me and I’m happy to explain.

RP (which includes sitting, standing, walking, and to some extent, running) must be formed through 2 mechanisms:

Release

Changes in perception

When we voluntarily perform an action, we are using the alpha motor system and phasic musculature.

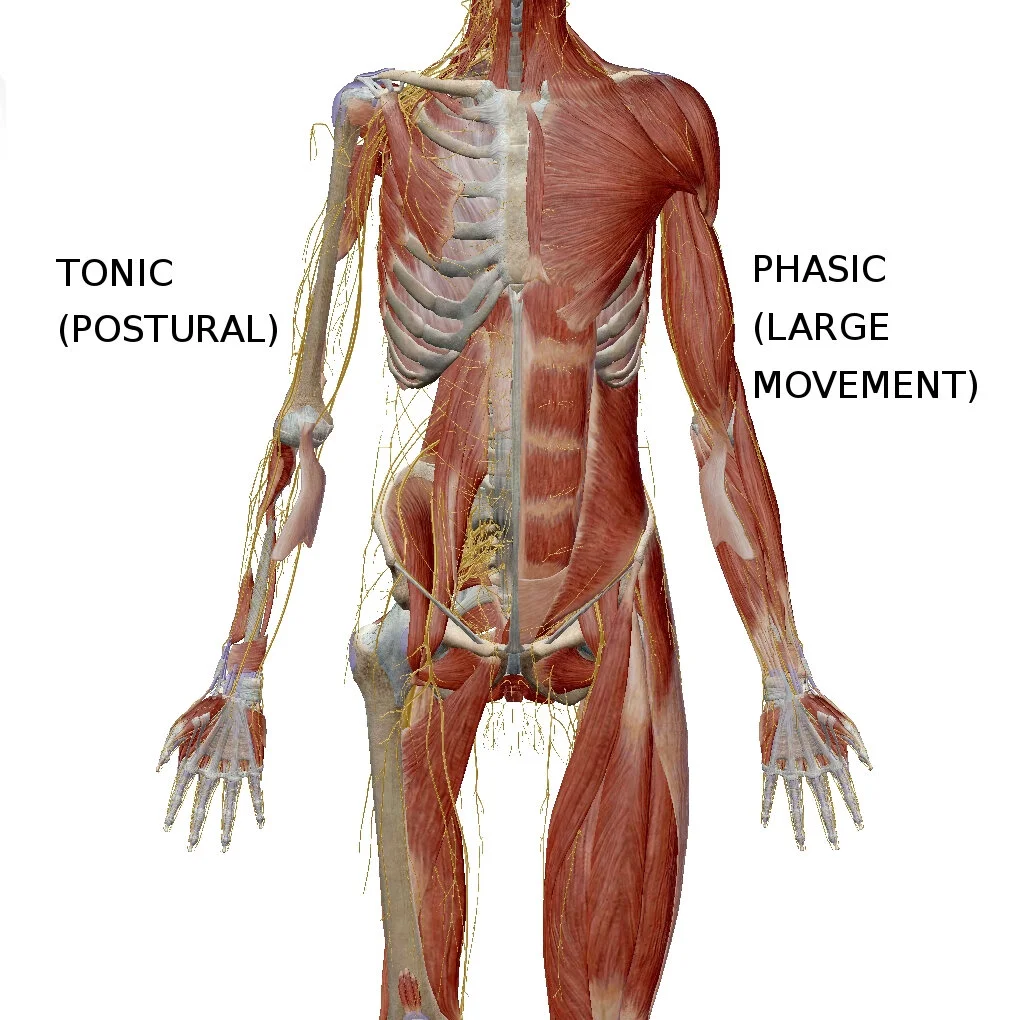

Phasic muscles are the large muscles we think of when we think “muscles”: pectoralis major, trapezius, erector spinae group, latissimus dorsi, gluteus maximus, etc etc. These tend to be large and long muscles, with a long moment arm in order to generate force and movement. The name “phasic” refers to the fact that these muscles are meant to be used intermittently. When they are chronically engaged, they are typically the muscles that become tight and cause us to be pulled out of “good posture”, which simply means a body position that increases the effect gravity has on us, making us have to work harder rather than relying on our skeletal system.

Most people who train in any capacity have heard of reciprocal inhibition, the idea that if you contract one muscle, its antagonist becomes inhibited and turns off. This is true in a stretch reflex, but most of the time not in contraction because of the way the alpha motor system works. So if a person’s pecs are tight, engaging the middle trapezius and posterior deltoids does not, in fact, turn off the pecs. Try it. Instead, what is created is tension on both sides of the joint, like 2 large weights on a see-saw, increasing coaptation (compression) of the joint. There is no “good posture” aside from one that is efficient, and obviously having muscles fighting each other is inefficient.

The solution then is to start by turning off phasic muscles that are working too hard to allow tonic muscles to take over. Tonic musculature tends to be primarily slow twitch fibers, across short moment arms, close to the center of the body or joint. It is intrinsically more efficient. Serratus anterior, rhomboids, transversospinalis group (includes multifidis), teres major, deep 5+1 lateral rotators, are the respective tonic analogues for the listed phasic muscles, but this is in no way a complete list. By getting these muscles to work in RP, the phasic musculature which has been creating a cascade of tensions to stay upright can begin to turn off, allowing for freer movement and increased efficiency, and typically better blood flow and nervous system activation levels. This is the release aspect of RP.

**tonic and phasic muscles are just ways of grouping muscles by function for ease of comprehension, not particularly rigid categorizations, but a useful way of viewing the body.

In terms of perceptual shifts, this is two-fold. I personally believe that many of the corrective exercises for posture (most commonly cervical flexion) are of more use as awareness tools, creating increased synaptic (nerve) flow to underutilized tonic muscles and giving proprioceptive information to the mind to allow it to create a better body map and naturally adjust to be more efficient. Systems tend towards a lower energy state, we just mess it up by interfering in ours. So when a part of our body ceases to be useful (like if the head is hanging so far forward that sternocleidomastoid and upper trapezius have locked it in place and all the deep muscles have turned off), our brains reduce nervous input from it to save energy. To change this pattern, awareness must be restored to the entire body.

The second aspect of the awareness bit is a perception of movement through space. When we create movement through awareness and orientation to space (reaching vs pushing) the gamma motor system takes over. The gamma motor system does create reciprocal inhibition, and also tends towards lower energy states by using tonic muscles and slow twitch fibers. So rather than “tuck the chin” as a cue for cervical flexion in a person with extreme forward head carriage (creating our compressed seesaw effect), a cue of reaching into space with the crown of the head will accomplish the goals of engaging longus colli and longus capitis, while also helping to reduce tension in their antagonists and create an improved spatial awareness, allowing for space in the joints.

There is also a psychosomatic component of posture tied into perception, but it is difficult to discuss and ultimately, so personal that I don’t think writing about it is particularly useful.

A brief example: erector spinae group versus transversospinalis group. FIGHT!

Let’s use a model of a slouching common man. The idea to actively straighten up has merit, since that is the ultimate goal to stack the body over its center. A slouching person will have tightness through the anterior (front) surface of their body, and for the sake of this example, lets oversimplify and say it is in the rectus abdominis (the 6-pack muscle). If, rather than utilizing release or a change in perception, our sloucher just starts to do back extensions and pulling themselves up with the back, they will use the largest muscles that can serve their purpose to overcome the tension, and engage the erector spinae group. At best the posture will only improve while they are actively engaging, at worst they will create a habitual holding pattern now on 2 sides of the body. The erector spinae group is a large, long band of muscle(s) that does not allow for fine segmental control of vertebrae. With these muscles holding the spine in gait, rather than the spine undulating and conserving energy and opening and pumping blood and spinal fluid, it is a rigid column that compresses constantly, with nowhere for the energy to go. (Look for a post on the dual function of the spine as column and whip at a later point).

If our sloucher works to release the front of the body, and orients toward space and begins to understand where their weight is being held, then transversospinalis group takes over. These muscles are multitudinous and connect from each vertebrae to the 4 or so above them, allowing for segmental stability, mobility, motility. Because their lengths are so short, they are super efficient and quick to adjust. Again, this is for resting posture. These muscles are not designed for deadlifting 450 lbs, but they are the right muscles for the job in gait because they allow for the wave of walking to travel up the spine, conserving energy and expanding the body from the inside out.

So, how to accomplish this? Well, the tools are ultimately inside of you. Realistically however, it is significantly easier with the help of bodywork, and more specifically, something like rolfing® structural integration. By facilitating both awareness and release, a bodyworker can act as a teacher on the path to having the tools to create ease in your own body. Combined with a trainer who understands the difference needed in between the way you farmers carry and the way you walk down the street, it is possible to go a long way, past the point where much external guidance is even needed anymore. If you are still going through the same issues and exercises with your bodyworker or trainer for 10 years, they likely aren’t helping you progress. It is our job to be educators, not mechanics.